Reviews

Inside Paul Klee's Irony at Work Exhibition

"The conviction that painting is the right profession grows stronger and stronger in me."

By Ode To Art

"The conviction that painting is the right profession grows

stronger and stronger in me."

- Paul Klee, Diary, N. 93, March 1900

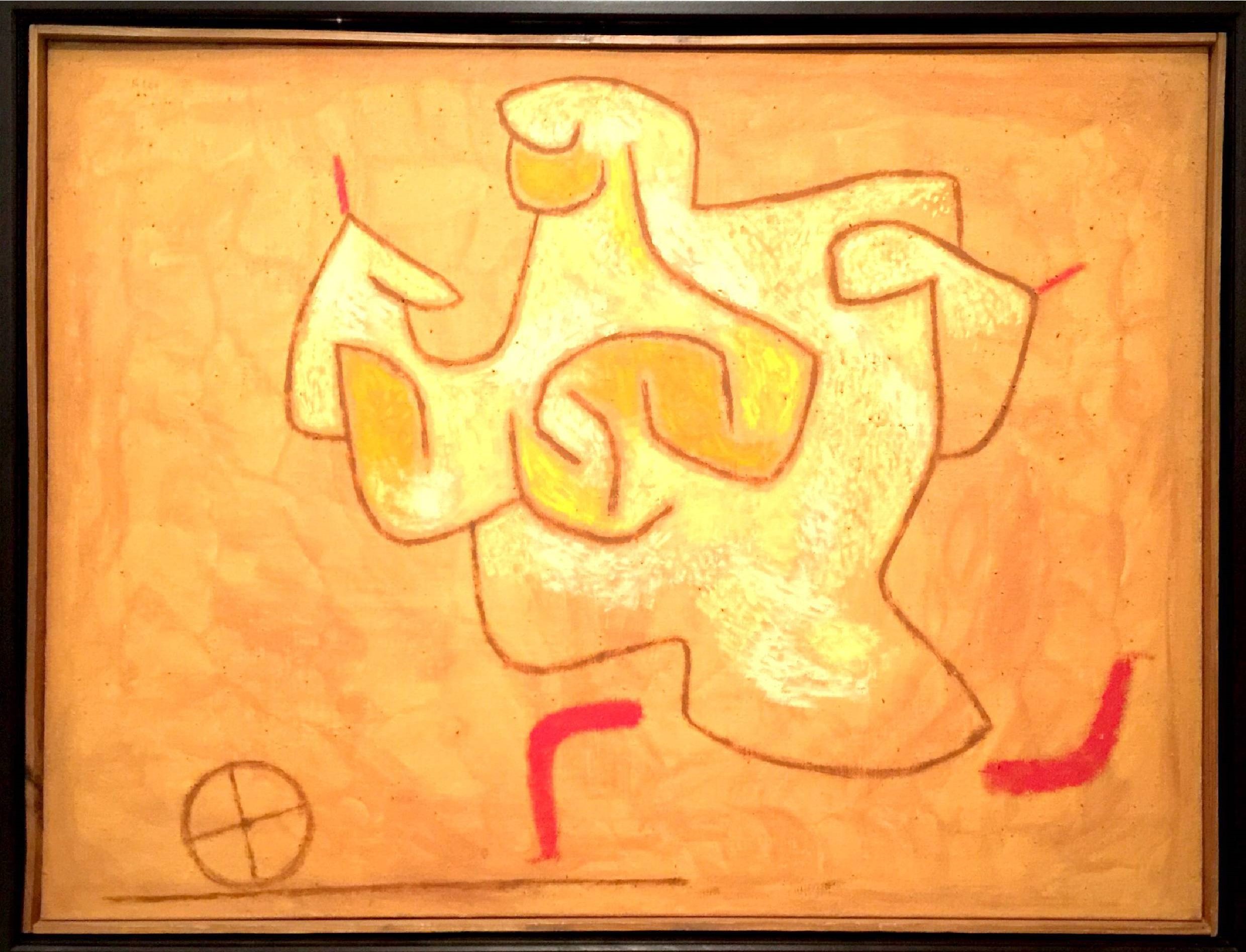

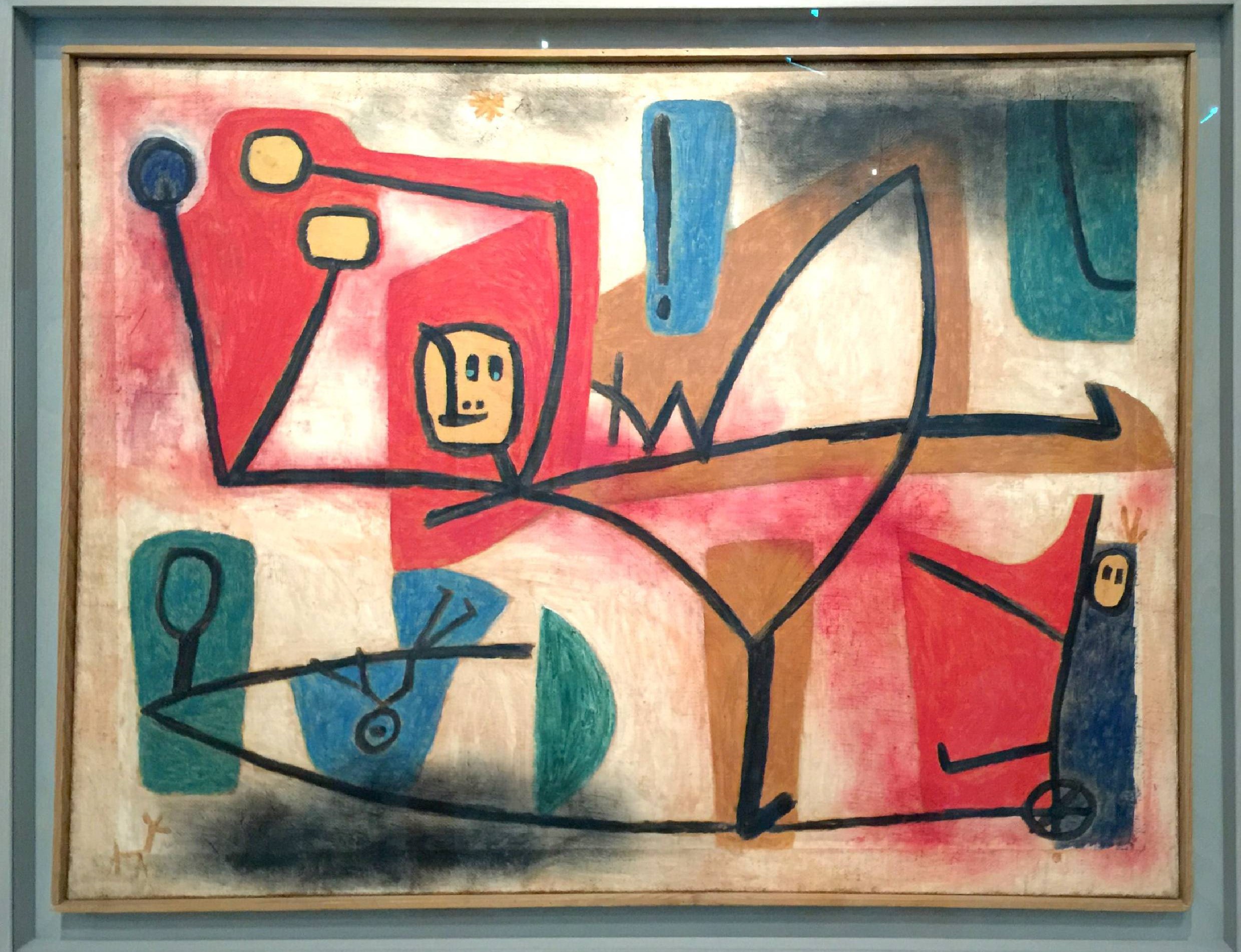

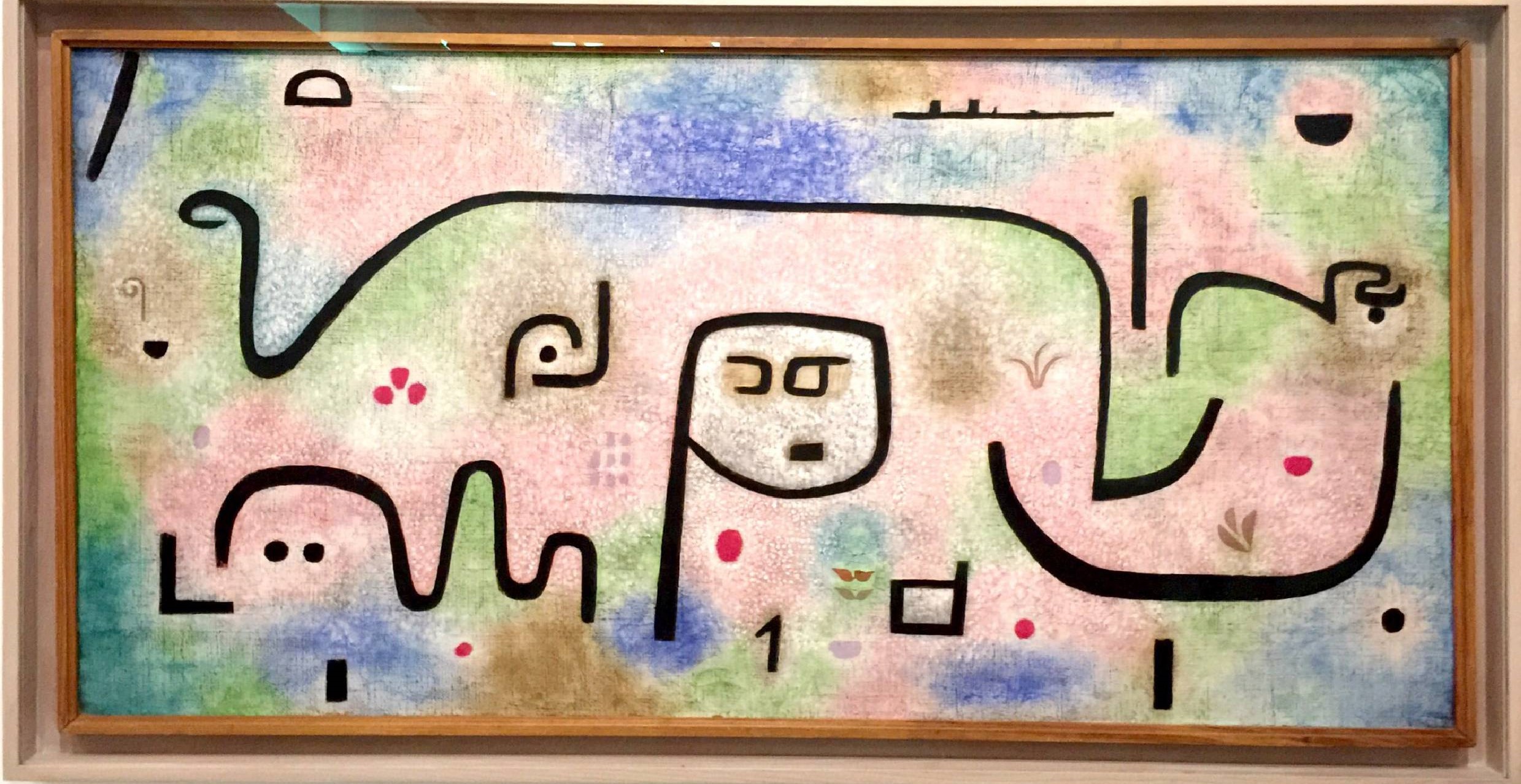

Originating in early German Romanticism, this satire and detachment enabled Paul Klee to be creative and paint whilst at the same time denouncing the policies and ideologies of his time.Helmed by some as the Father of Modern Art, Paul Klee’s art has intrigued, fascinate and surprised at least three generations of art lovers and collectors around the world. I have last seen this Swiss-born artist’s works in Tate Modern’s Making Visible exhibition in 2013 and was delighted to find the retrospective by Centre Pompidou in Paris more comprehensive.

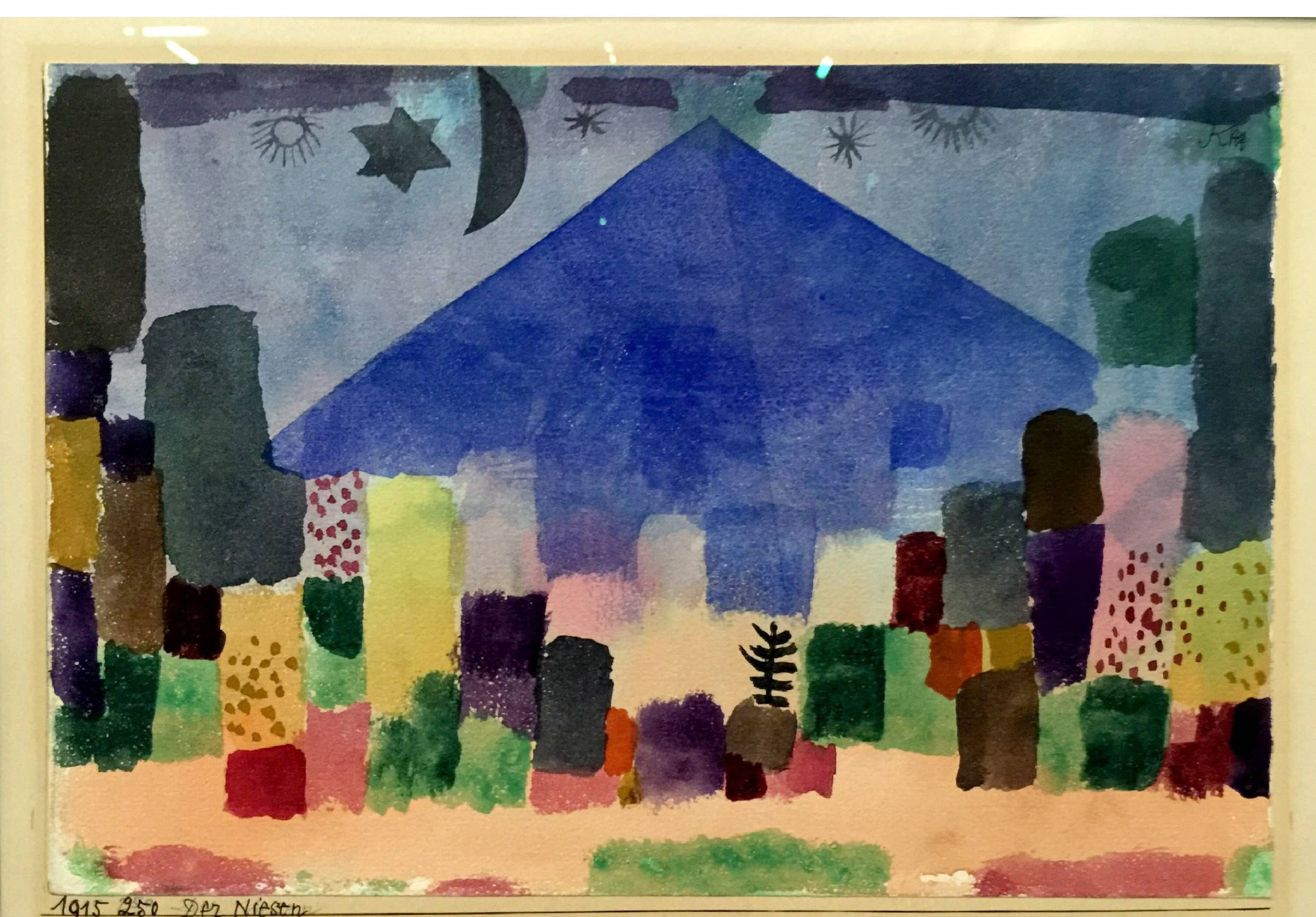

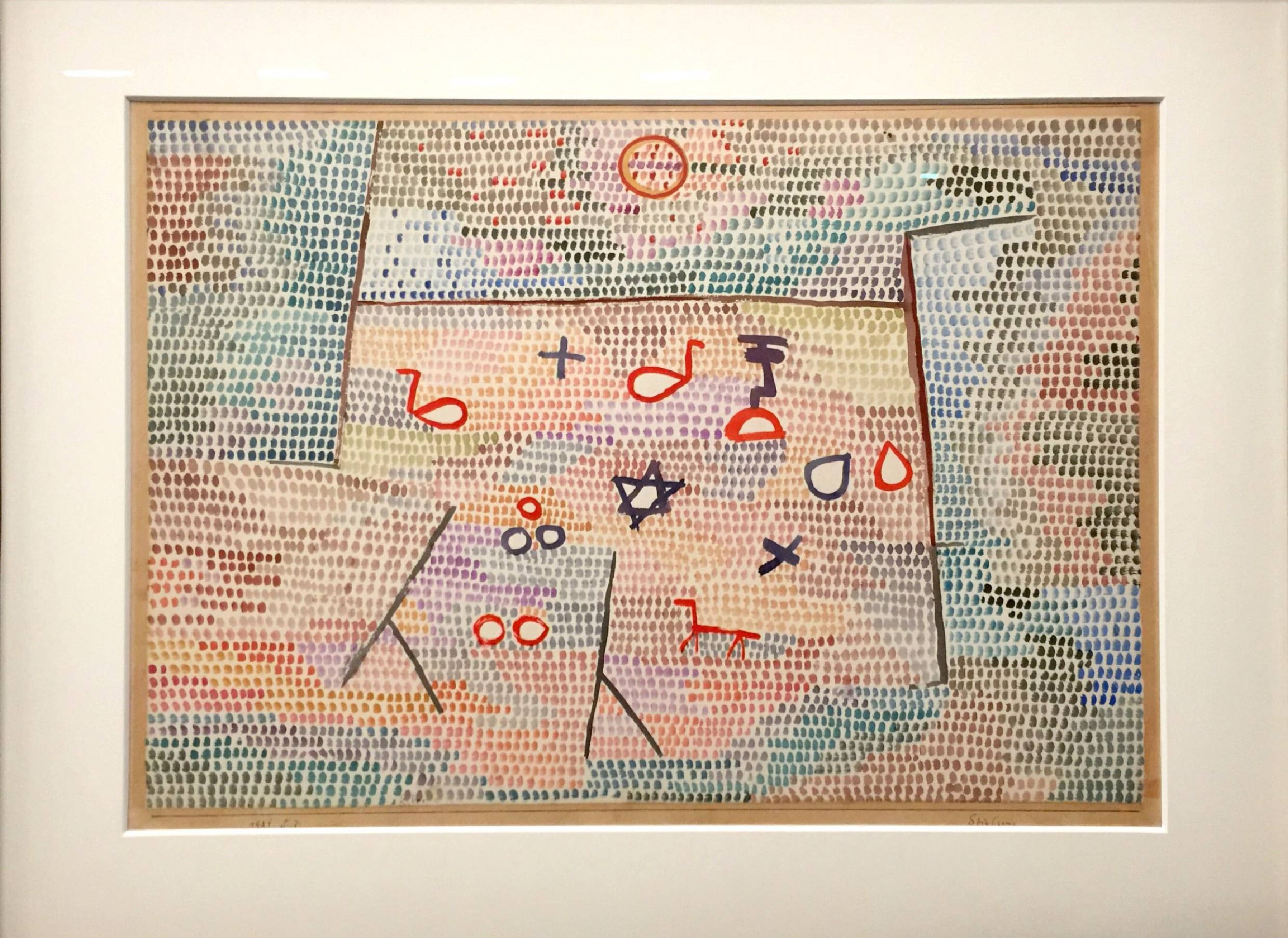

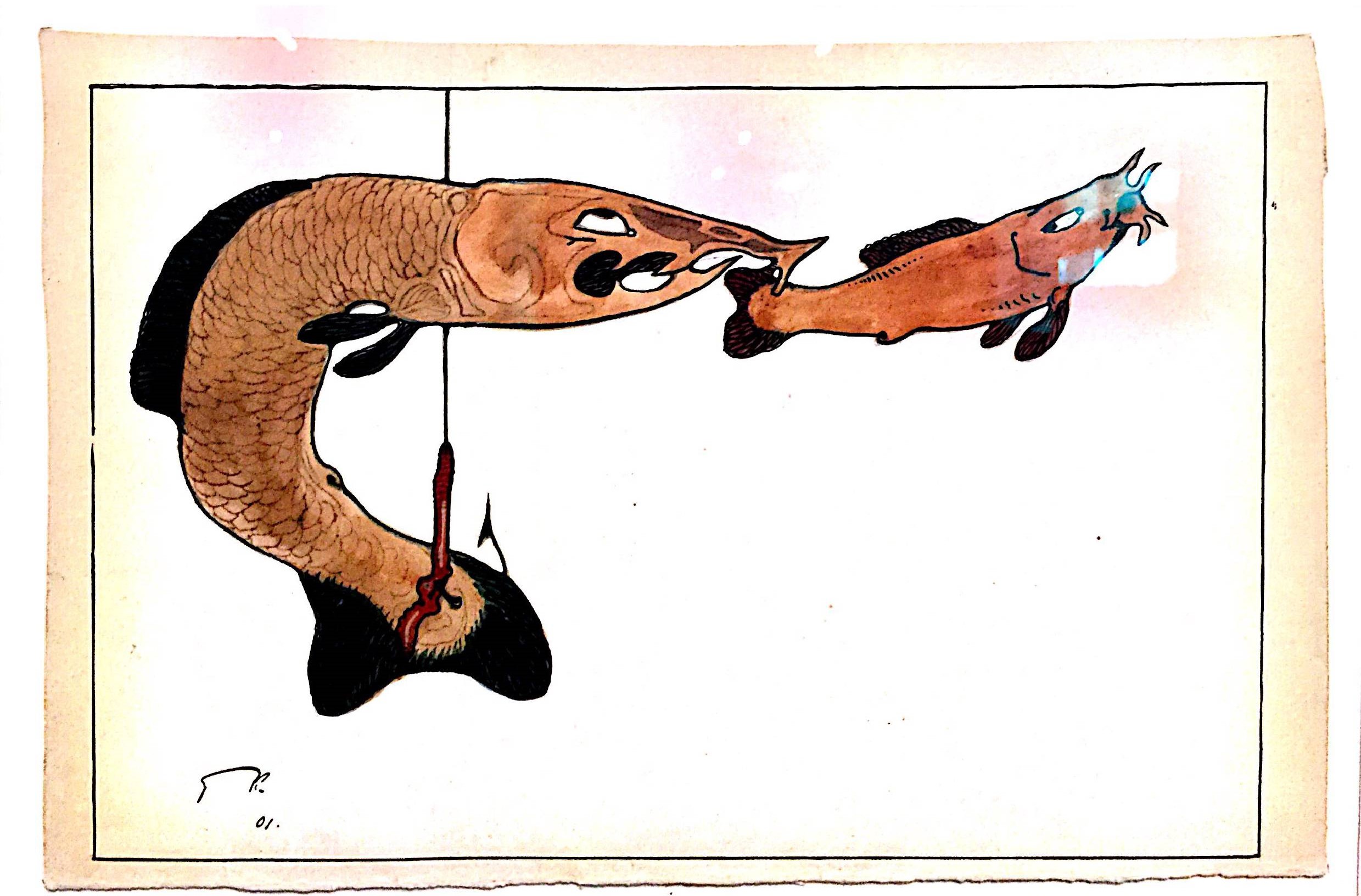

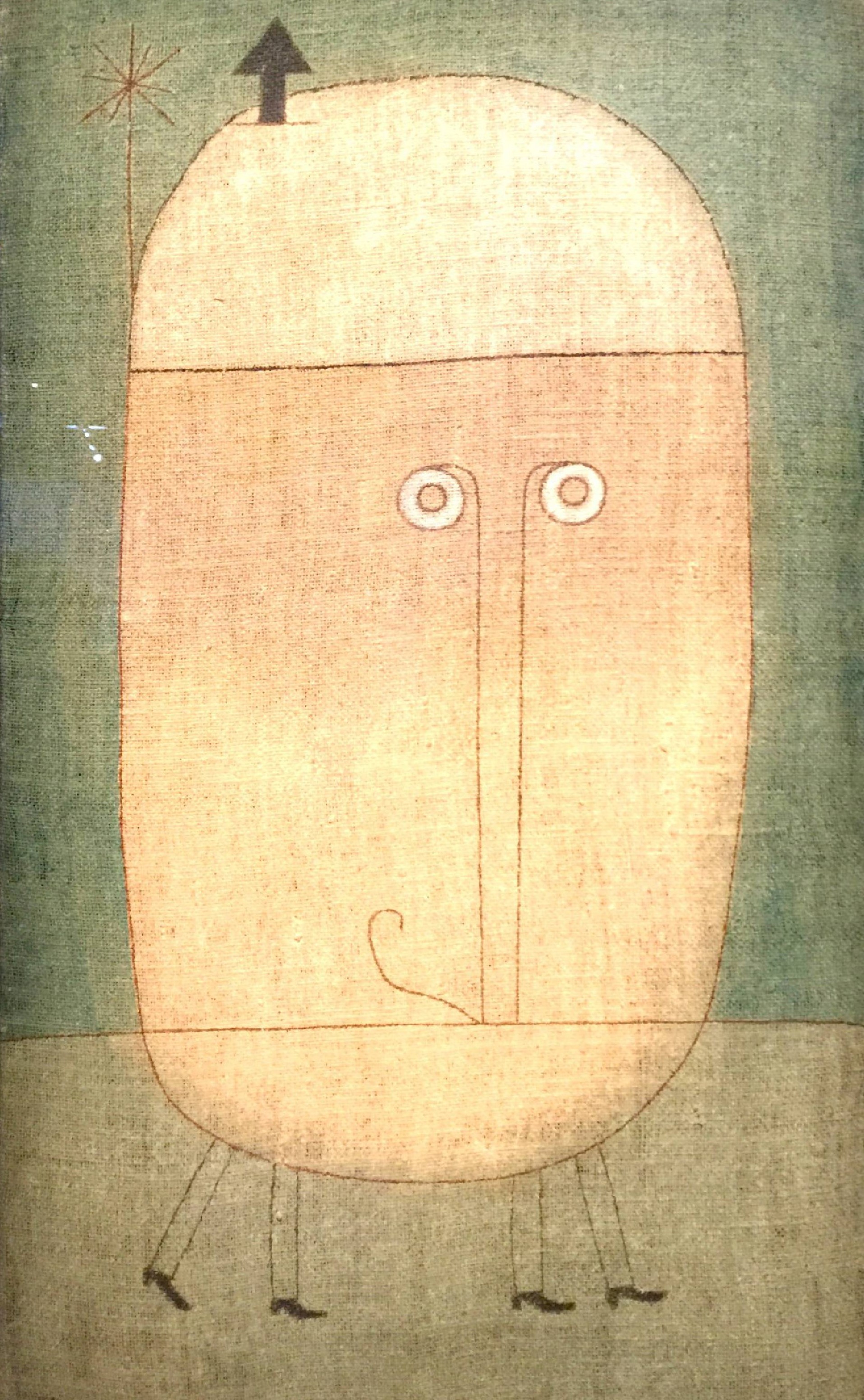

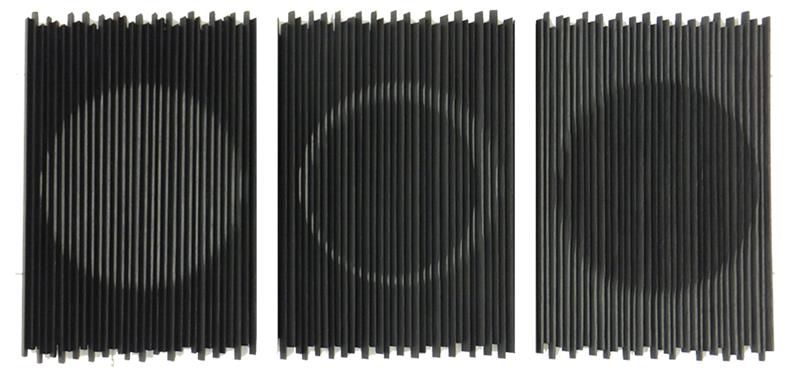

Titled L'ironie à l'oeuvre (Irony at Work), this retrospective is curated around seven themes: Satirical Beginnings, Klee and Cubism, Mechanical Theatre, Klee and Constructivism, Looking Back, Klee and Picasso and Crisis Years. The clear and precise themes created a journey down memory lane retracting the key milestones in Klee’s lifetime. One would recognize his works which commonly featured simple stick figures, moon faces, suspended fishes and quilts of colours but to walk along 250 works created in different periods of his life has allowed visitors to be on a time capsule to where his art journey began and eventually ended.

Seemingly simple and childlike, the expanse of his works is a reflection of a system he has internally built during his career. Often time ironic and satirical, the retrospective emphasizes again and again on Klee’s intentions from the titling of his works (he was preoccupied with the arrangement and ring of words) to the cataloguing of his works. His titles guided us to see works he had purposefully set up be it irreverent, deadpan or poetic. From small watercolour sketches to bigger and older works, we were prompted to take a fresh look at them, taking his “Romantic Irony” and associated ideas of satire and parody across the range of his works.

After all, Klee was one of the few artists that denounced socially established standards and dogmas established by his contemporaries while applying his own rules and principals onto the works. He played the parts of monk and actor, oscillating between assertion and negation, continually refining a strategy based on a play with antagonisms. To him, art ought to be “a game with the law” or “a flaw in the system” and this, is what makes him a singular figure in modern art.